Swiss design – a tradition of change

Swiss design is known far beyond its borders and reflects the diversity of the country. From highly functional to expressive, its development is closely linked to Switzerland's economic and societal changes. To understand the success of Swiss design, it is worth both looking back at industrialisation and considering the significance of sustainability in modern design practice.

Diverse Switzerland – diverse design

When we talk about Swiss design, we have to talk about diversity: Switzerland, this small country, has four language regions. It has neither a homogeneous national culture nor an undisputed national identity. This is also reflected in the design. It ranges from highly functional to extravagant forms. German-speaking Switzerland is more influenced by the functionalist debate, while French-speaking Switzerland tends more towards an understanding of design that focuses on expression. In Ticino, design is oriented towards the formalised design tradition of Italy.

Until the 20th century, poverty was widespread in the country. This only changed with the invention of the steam engine, the water turbine and consequently electrification. The steep mountains supplied the young industry with hydroelectric power. A little later, the development of the industrial and service sectors had irrevocably changed the agrarian society. The shaping of change led, as elsewhere in Europe, to the founding of arts and crafts schools in the 1870s: The government supported training in arts and crafts so as not to lose touch with other industrial nations. The schools had to provide the growing textile and watch industries with capable designers. The arts and crafts orientation favoured jewellery, tools, interior design, furniture and typography. Today, Switzerland has no less than seven renowned universities offering education in all major design fields.

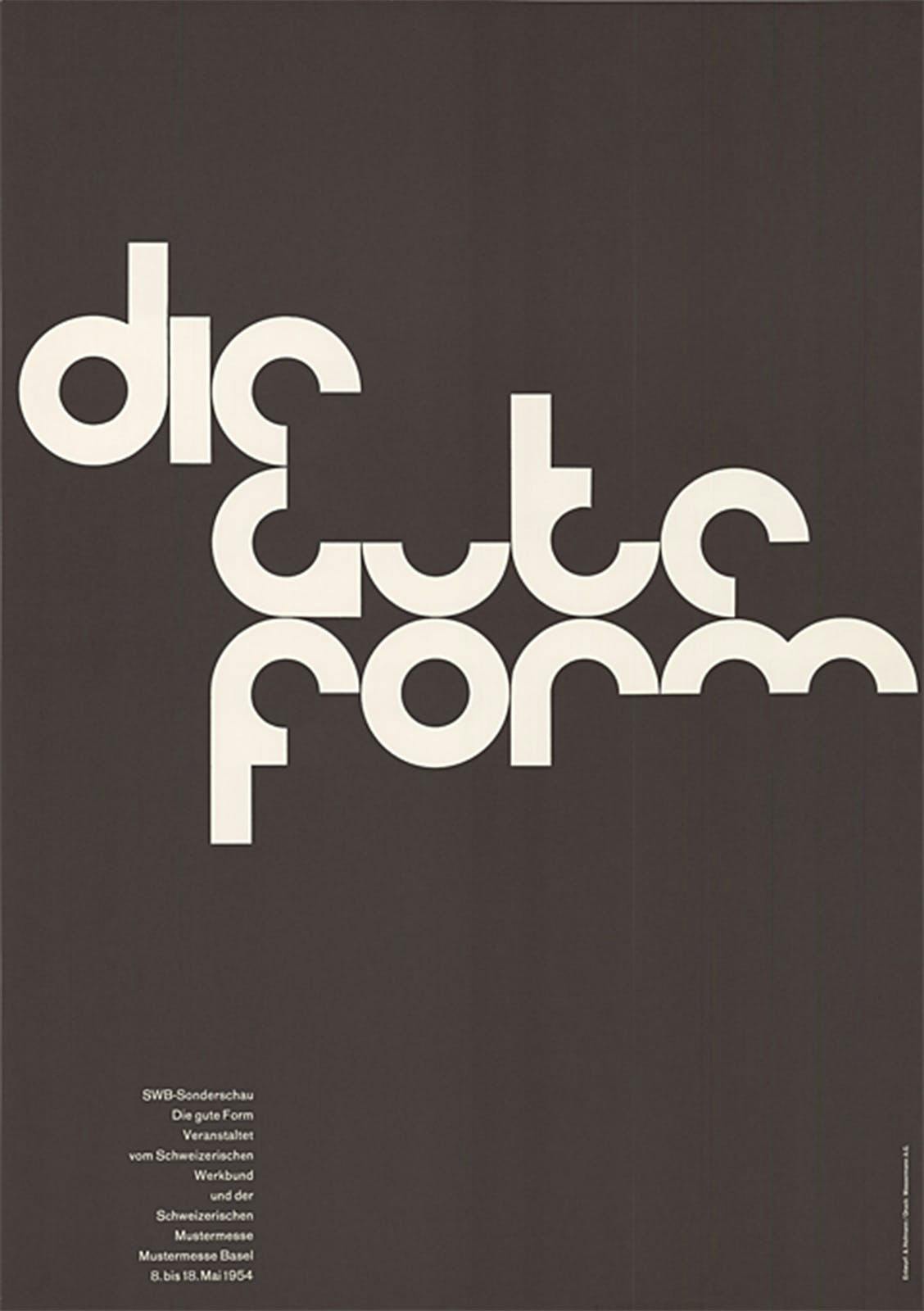

«Die gute Form»

After the Second World War, designers and manufacturers were able to catch up with the international competition thanks to a production landscape untouched by war. The German «Wirtschaftswunder" of the 1950s and 1960s also helped the Swiss economy. For many, this opened up the possibility of working in an increasingly international industrial sector. In the 1950s, Max Bill coined the term "die gute Form" (the good form). A paradigm that according to the elitist and humanistic self-image of its time should be both taught and learnt. Until 1968, the Schweizerische Werkbund, with its eponymous design prize, offered orientation during an era when unparalleled economic growth led directly to the boom in consumer goods. Today, the key features of the good form - balancing form and function - remain an important part of the DNA of contemporary Swiss design.

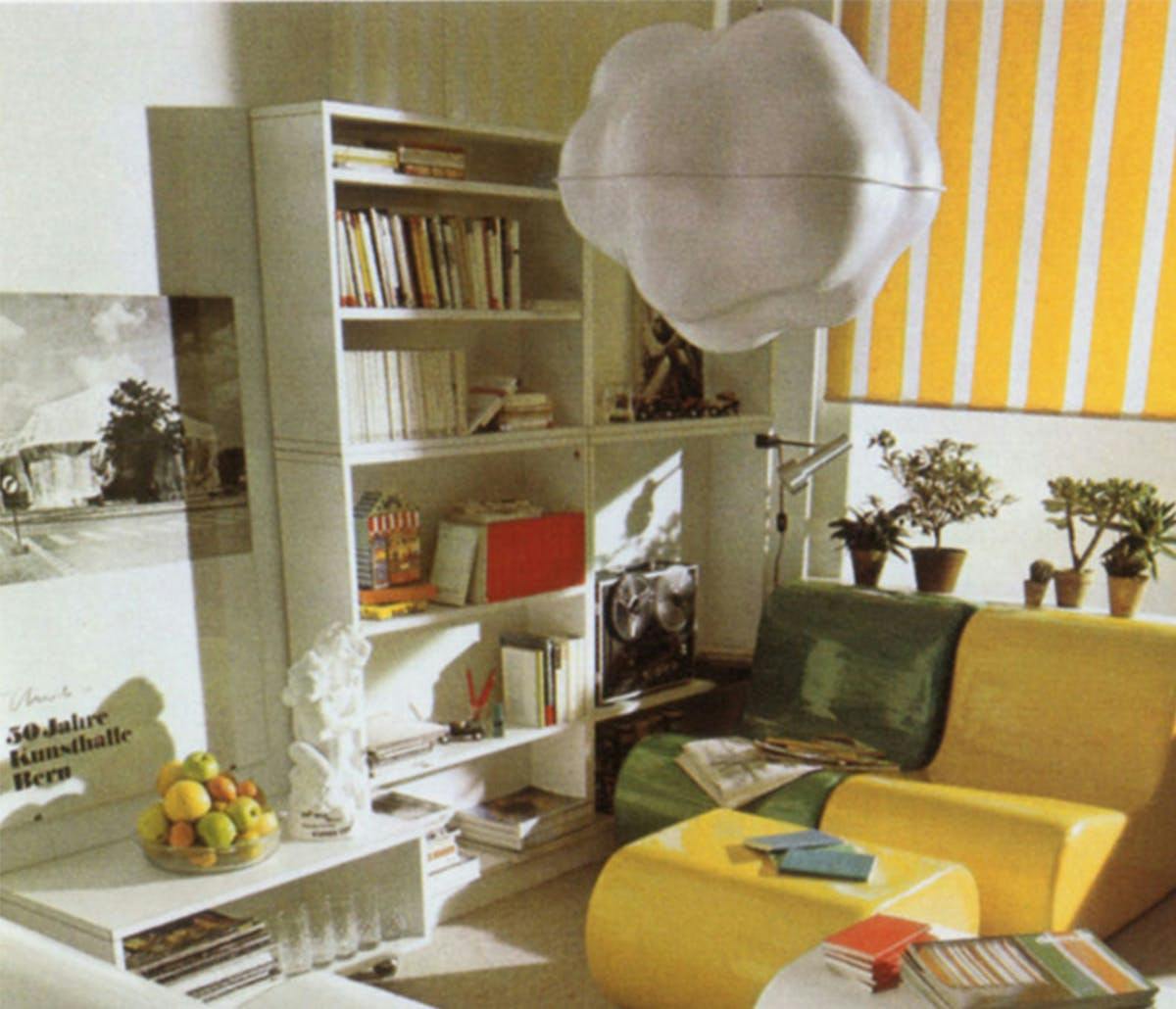

However, in the 1970s, a new generation of designers challenged the functional rationalism it propagated. They introduced concepts such as ecology, emotion, irony and symbolism into design. The "Wolkenlampe" by Susi and Ueli Berger, designed in 1970, stands for this changed conception of design. It is not only a lamp, but also an image: "Ceci nest pas une lampe". As such, it is the opposite of what has previously been labelled "the good form”.

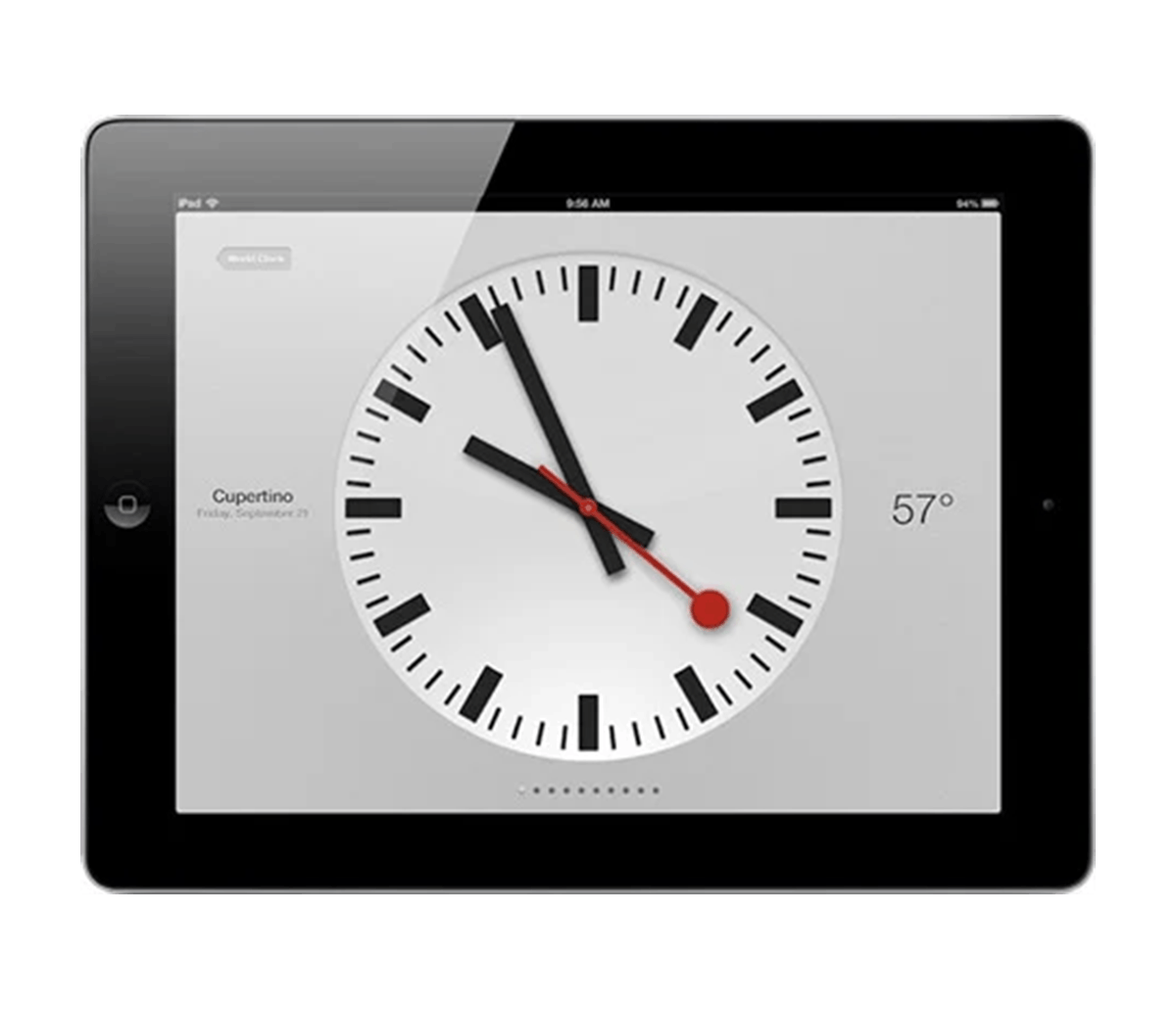

After all, there is no country without ornament or symbol, not even rational Switzerland. For example, the red trowel that Hans Hilfiker used as a second hand in his station clock. He designed it in 1955 for the Schweizerischen Bundesbahnen - and it may be the origin of the cliché of the punctual Swiss. Since trains always leave the station at the full minute, the second hand had to be easy to read from a distance. It imitates the signal disc with which the stationmaster once waved the trains out of the station. More than half a century later, Apple used the iconic design of Hilfiker's station clock on the iPad and iPhone - and infringed copyrights in the process. In the end, Apple paid royalties of around $20 million and then stopped using the design. This little story about symbols and design shows that good design has long lasting value.

Breaking with tradition

Let's stick with the clock: In the 1980s, cheap Japanese quartz watches almost drove the conservative Swiss watch industry to extinction. The sale of mechanical watches plummeted; the demand for precision watches hit rock bottom. In 1983, Nicolas Hayek, the founder of Swatch, broke with tradition and initiated the development of a watch that could be produced millions of times on fully automated production and assembly lines. The Swatch was given a face by Swiss graphic designer couple Jean Robert and Käti Robert-Durrer (the parents of Alex Robert, co-founder of FOND Design) that perfectly captured the lifestyle of the post-modern 1980s. Today, the Swatch Group owns 18 watch brands, including luxury brands such as Omega, Blancpain and Breguet.

Just like the watch industry, the textile and clothing industry was in similar bad shape in the 1980s: Production had been outsourced to low-wage countries in order to optimise profits. Whether out of short-sightedness or pure greed, the technological know-how was exported along with the weaving machines, further weakening the Swiss production location. Today, the textile industry survives through technological innovation and differentiation in the market. It ranges from highly specialised technical textiles to haute couture. Design is a decisive factor here. Thus, companies invest in new technologies, materials and finishing products.

Cornerstones of Swiss design

The four cornerstones of Swiss design are engineering-driven perfectionism, meticulous work in all details, a willingness to innovate and consistent user orientation. Design from Switzerland resists short-lived solutions and wasteful consumption. By consistently asking the right questions in the process, it builds on the needs of the people using it - then as now.

This is where the practice-oriented education and the Swiss Design Association come into play. Since 1966, the professional association has championed design, which is created in a privileged and rapidly changing economic and cultural environment. Deindustrialisation and digitalisation have fundamentally changed design processes and thus the design profession over the last 30 years. Designers have long acted as generalists, drawing on their broad skills. But this holistic way of thinking is now recognised and adopted by many professions. Economists call themselves design thinkers and engage in design management. Complex digital technologies and systems, however, also require design specialists. Job descriptions such as UX and UI designer, interaction and game designer, business and social designer are numerous. And more will emerge. In this context, design generalists and design specialists work in multi- and transdisciplinary teams with other experts. Accordingly, a multitude of authors are involved in the act of inventing a new form or a new concept. Design becomes anonymous and authorship less important.

A future based on a tradition of change

In an increasingly deindustrialised Switzerland, we are moving from a product-driven society to a world in which knowledge and services are central. The object- and author-oriented paradigm of design is giving way to the understanding that design can be described as a contextual process - applicable to entirely new fields such as legislation, culture, public service or policy making. Design is no longer just about a beautiful vase or a chic chair. In the right environment, design drives innovation in all areas of value creation. This includes not only monetary, but also social and cultural values.

The design community worldwide has been proposing ecological, circular and sustainable solutions since the early 1970s - without significant success. Neither in Switzerland nor elsewhere does market self-regulation alone lead to a more environmentally friendly future; on the contrary. In order to achieve the transformation to a more sustainable world, design is dependent on guidelines with broad backing. It needs societal pressure to realise clean, environmentally friendly, inclusive and sustainable goods and services. Design as a service is always built on external requirements. Manufacturers and service providers need to involve designers accordingly, and if not out of conviction, then at least out of self-interest, in order to respond to economic, social and regulatory change. Only then can we hope to create a sustainable world based on a tradition of change.

This article is based on a keynote speech given by Dominic Sturm, co-founder of FOND Design and president of the Swiss Design Association at the World Eco Design Conference 2018 (WEDC) in Guangzhou, China.